Spotted in Bell, Book, and Candle, 1958.

Thursday, June 10, 2021

Wednesday, April 28, 2021

TI-99/4A Play-and-Display

As I got older I regretted that the TI was gone. That computer meant a lot to my father and he worked hard to save to get it. So, this year I decided to find a good example and dedicate a space in my office to recreate what I remember of that vintage computer. I specifically wanted to have a nice display for the unit and a way to keep all the associated items in one place. The 99 uses cartridges for many programs so having storage for that would be helpful.

|

| TinkerCad is a great! |

Not having a monitor or a spare TV I decided to use one of those cheap backup camera displays. They are native RCA and the price was right. I was even able to drive it off the 12v line coming form the video port. I think there is some noise on the signal, but for my purpose (casual use at best) it was just fine. There would be room on the back panel area to mount a small flat panel TV and I might do that in the future.

Sunday, April 25, 2021

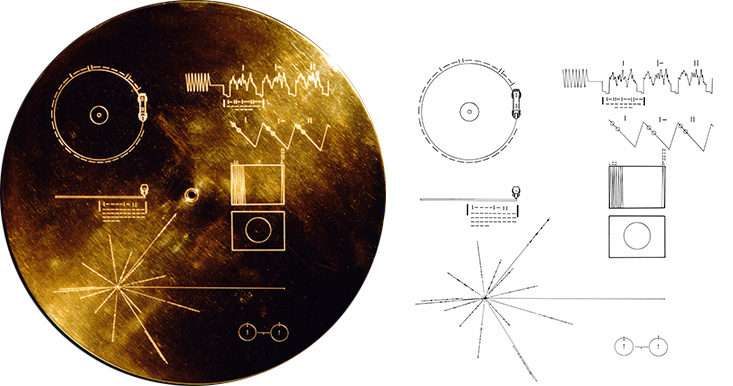

Offworld Communication

Sometimes you get lucky. I was lucky when I found this calculator:

I was excited by this find. You don't find many of these in the calculator bins at thrift stores because the internet has made them famous. They are easy to get, but not for $3.00. The 11C (from the Voyager series) was a mid-range RPN programmable scientific. This one was made around 1987 and while used, it is clean and works really well.I have another Voyager series calculator, but it's the more common (and still manufactured) 12C Financial. The 12C is a hard calculator to like because of late-stage capitalism, but the 11C is filled with scientific goodness. Sine? Check. Statistical analysis? Check. Programming? Check. This little gem has it all.

As I was enjoying playing around with these marvelous buttons, I started thinking about the back of these little wonders. Why the back? The back is covered with information engraved on an aluminum sheet. The back serves as a cheat sheet of sorts; offering guidance on how to program the device, common error codes, battery size and orientation. It's delightfully empty of words instead relying on the dual universal language; images and math. I took the time to search through the manual to understand it and make this information graphic:

The cover and the contents of the record says more about us as humans than it could ever say to a distant people. Sagan likened the record as a note in a bottle. It may reach far distant shores or it may be lost in the vast unknown. Both are possible, but we hope the bottle lands none-the-less. We know that the record is there. We know that the information lives on. We know that something of ourselves is out there. It's as romantic and artistic a view of space travel as we are likely to get from scientists. (Unrelated, send poets and artists into space, not just scientists.)

Tuesday, April 20, 2021

Parts from the Future

Back in July of 2020 I got a call from Bill Wahl of Mesa Typewriter Exchange to let me know that the IBM Selectric I dropped off was done. There have been a few of these iron giants in my collection from time to time, but this one is the one I keep. While not particularly pretty (Like Teds blue-key beauty), it’s clean and a good size. Sadly, it had developed a bad case of Selectric thumping and was giving me some problem with the ribbon advance mechanism. This one uses the carbon ribbons. Both of these repairs are not in my bailiwick so to Bill it went.

Bill replaced the cycle clutch pulley gear with a new non-broken one. For anyone who has ever owned a thunking Selectric, you know that it’s a matter of time until this part breaks. Age is the culprit. Time is not kind to the plastic and it becomes brittle. Sometimes you can repair them with epoxy and binding wire, but replacement is the only guaranteed option for trouble-free typing.

With all the OEM parts used up or aging and cracking on their own, modern manufacturing processes can breath new life into these typewriters. Bill gave me a small tour of the two types of replacement pulleys available today. One is CNC milled aluminum and the other is 3D printed.

In the picture above, you can see the CNC milled aluminum example (top) and the 3D printed one below. The original cracked part is brown. Having used the aluminum parts initially, Bill prefers the 3D printed ones; they are less noisy.

Both of the replacements pulleys need a donor arbor to mount them properly. The new pulley feels like sintered nylon to me, but it might be another material. Regardless there is a heft to this replacement part that makes it feel like a quality item. With only dozens of these parts in working typewriters the longevity is still an open question, but based on how mine works and sounds I think it works well and if something happens another one can be printed.

The promise of rapid prototyping and the 3D printing makes it possible to keep our old typewriters running. It only takes someone who knows what they are doing and cares enough about our magical writing machines to help keep them humming along sans thump.

Saturday, April 10, 2021

Wheelwriter Wheels

Wednesday, March 10, 2021

Vintage Technolog Book Club: King of the Seven Dwarfs

|

| Fig 2. ERMA |

I can imagine that on the last day of work Kathy (The name written in sharpie on the bottom) decided to slip this three-hole punch into her box of belongings and left GE for good. Was it in the 1970s when GE Phoenix was taken over by Bull? Was it her favorite three-hole punch? Why the orange? Can you believe this isn't the first one of these I've seen around here?